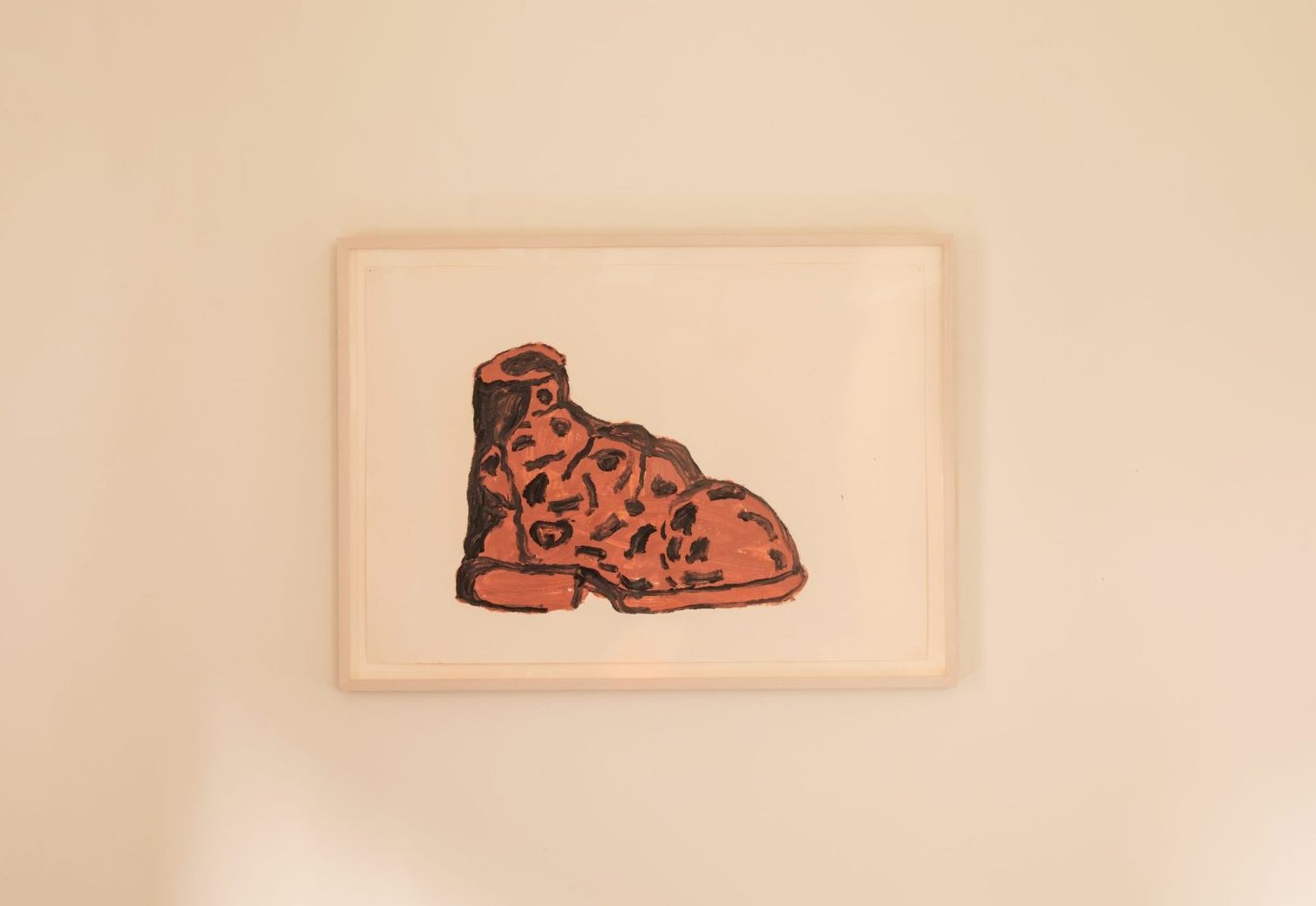

“Broken Floor”, 2022

Mount St. Restaurant floor

American artist Rashid Johnson has transformed the floor of Mount St. Restaurant into an enveloping site-specific commission, made of exquisite shades of Palladian marble, that allows guests the opportunity to experience an artwork differently – they are able to dine on it, walk on it and dance on it! The design for the mosaic, titled ‘Broken Floor’, was inspired by his ‘Broken Men’ series, which deconstructs images into fragmented pieces. These works reflect on the current discourse of the human condition, how we are exposed, where we fit into society and gender bias, but they also offer a spiritual journey of how to fit these pieces back together and reconstruct ourselves.